Hi grads (and other readers)!

In our last SGTA seminar, we talked about burnout, where it comes from, and how to mitigate it. If you couldn’t attend the seminar, don’t worry. Here are some of the key takeaways from our discussion.

First and foremost, what is burnout? It’s a feeling of mental, physical, or emotional exhaustion – sometimes all three. You might feel unmotivated or cynical about your work, be it GTA duties, coursework, or research. You might feel like you can’t get it all done, so there’s no point in trying. But burnout isn’t just tiredness or laziness. It’s not even just stress. Burnout is a function of your expectations – both those you place on yourself and those others have for you – and your self-efficacy. This is the belief that you can achieve the things you set out to do, or to complete the tasks you need to be done.

Let’s talk about expectations. Often, burnout arises from a mismatch between expectations and reality. For instance, if you expect to sit down and complete a weekly homework assignment in one hour, and it ends up taking many, many more hours than that, it makes sense that you may feel overwhelmed, frustrated, or cynical about the work you are doing. Perhaps you do have realistic expectations for yourself, but you feel that others do not. Maybe your research advisor expects you to work more independently than you feel ready to in this part of your research journey, or perhaps your teaching mentor asks to have lots of meetings with you throughout the week, but you feel pressure to use that time to be productive in other ways. These are also mismatches in expectations that can lead to burnout. These kinds of mismatches also impact your self-efficacy. Clearly, struggling to complete assignments on time can be draining – it wouldn’t be surprising to find yourself thinking, “If I was only better at this, I would be done by now and could move on to other work.” Feeling like you can’t meet the expectations of your mentors can also impact your belief in your research or teaching ability.

So, what can be done? You’re exhausted, a lot is being asked of you, and the to-do list is never ending. The Big One is to set realistic expectations. Rather than counting it as a success only if you complete your homework assignment, you might set the goal of sitting down and trying to understand each question on the homework – what definitions are involved? What sections of the textbook are relevant? What key ideas and theorems seem important, and what are the questions actually asking? Answering these questions is an attainable goal that moves you in the right direction. Similarly, be willing to have candid conversations with your mentors about their expectations. You might ask to have fewer meetings, or even ask to cancel one to take a mental health break. Your mentors are academics, too, so they know what burnout feels like. These are things you can do to help recover from burnout.

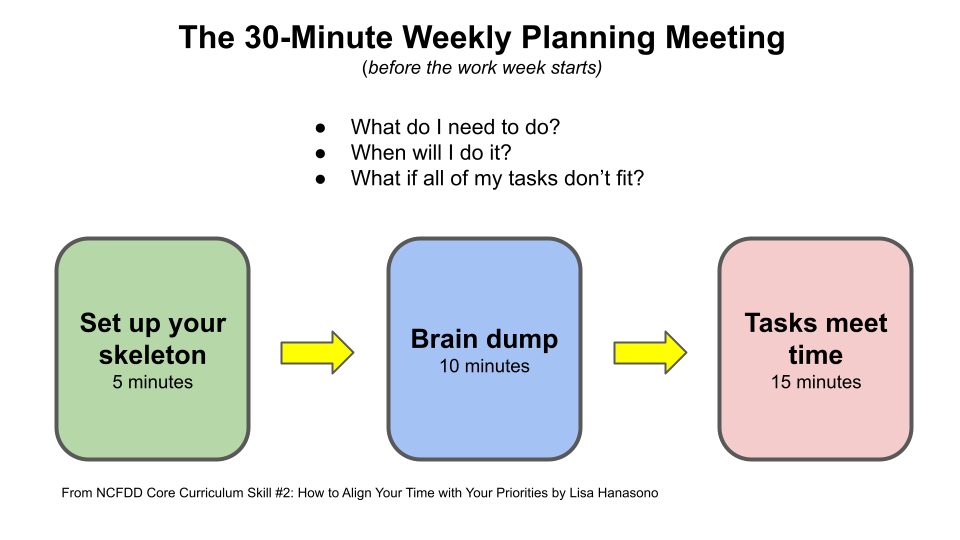

To mitigate it before it hits too hard, there are a couple of strategies you can try. The first is effective time management – its way easier to feel burnt out when you’ve procrastinated until all of your deadlines are right around the corner. One way that works for me is to formulate a weekly list of tasks I know I need to complete, usually on Monday when I come into the office. Then, each morning I select tasks from the list that I see as appropriate for the time I have to do them. This means that if I have 45 minutes before my next meeting, I’m probably going to choose a grading task over a homework assignment, which I know would take much longer. That way, I’m selecting tasks from a menu of things, and the time I have is used to actually check things off the to-do list.

You should also take meaningful breaks. Your brain works passively in the background when you’re engaged in other activities, so rest can actually still be productive. Even if it wasn’t, you’re a human who needs to rest. When i say meaningful breaks, I unfortunately mean not playing on your phone. If you’ve been working on a computer screen for hours, switching to staring at a phone screen puts the same strain on your eyes, brain, and body, even though it feels good because phones give us a little dopamine boost. You should take breaks that are qualitatively different activities than the work you were doing. Even just getting up and walking around the building for a few minutes before returning to your desk feels revitalizing. Some students plan a whole day (or even just a half day) to focus on resting, hobbies, or friends, avoiding math or work related tasks altogether. These break days are also much more beneficial when you plan to take them, rather than accidentally taking them because you wake up one day too overwhelmed and burnt out to do anything.

Finally, try to stop overcommitting. We all have responsibilities that we can’t say no to, but often we say yes to optional things because it feels good; we’re flattered that someone would ask us for our help or expertise. It might feel like an honor for someone to ask you to critique their paper or work on their problem, but you will have to do it in the future. Stop and consider whether this is really something you want to spend your limited time and energy doing. Further, if you overcommit and have to back out at the last minute, the people who were relying on you for that task will feel let down. It’s better to say no at the beginning than to say yes and bail.

I hope this has been helpful as you think about burnout, how to recover from it, and how to mitigate it in the first place. As you return to your work, try to set one actionable goal for the week to help mitigate burnout.